Horses being flight-or-fight animals are always prone to injury and as such are commonly affected with limb wounds. These limb wounds can occasionally penetrate to the bone and result in the formation of a sequestrum – a little piece of dead bone.

A sequestrum located in the left hind cannon bone (metatarsal). Image by Advantage Equine.

Sometimes limb wounds in horses damage or expose the bone, especially below the knee and hock where there is little coverage over the bone compared to the upper limb where substantial soft tissue and muscle form a buffer between the skin and the bone. These injuries can result in a sequestrum forming.

A sequestrum is a piece of dead bone that separates and lifts off the parent bone and becomes infected, causing the body to respond by mounting an inflammatory response. The body reacts to the dead bone as it would react to a foreign body such as a splinter of wood, by walling the area off and producing pus to help remove the problem.

Any wound that involves the surface of the bone can be at risk of a sequestrum forming if the surface of the bone is compromised and infection is present; but the skull and the lower limbs are more commonly affected, as the bone is very close to the skin and therefore easily exposed and damaged if an injury occurs. Sequestrums can also form on the forearms and sites like the ribs but do so with less frequency.

As bone is a living tissue, it requires a blood supply to provide its cells with oxygen and nutrients to keep them alive. Blood is supplied to a bone by vessels that are located within the inner marrow/medullary cavity or vessels that supply the outer fibrous covering of the bone, which is referred to as the periosteum. If the blood supply to a bone is damaged for an extended time or the bone is compromised over a large area and blood flow is significantly reduced, the cells in the bone can die, causing the bone to become necrotic and break off. Similarly, if an area of bone is fragmented off the parent bone and loses the blood supply from that bone, the bone piece will also die and is at risk of becoming a sequestrum.

A sequestrum on the right hind cannon bone (metatarsal). This sequestrum was cured conservatively (antibiotics and time, no surgery required). Image by Advantage Equine.

SIGNS TO LOOK FOR

Clinical signs that suggest the presence of a sequestrum include heat, pain, and/or a persistent discharge from the site of a previous injury or a delay in the expected healing time of a wound (a non-healing wound). A sequestrum can be seen within weeks of an injury or in some cases, several months after. In some cases, a wound will heal over, and the owner believes the injury has healed, only to find a sudden recurrence of swelling and pain over the site, with the old wound bursting open and a draining tract being discovered. Not all horses are lame when they have a sequestrum, and therefore, a sound horse does not mean there is no possibility of a sequestrum being present.

Diagnosing a sequestrum generally requires an X-ray to identify the dead piece of bone and the bony reaction that occurs around the sequestrum, referred to as the involucrum. An involucrum is the bone’s way of walling off the dead bone in a similar way to how the body walls off an abscess and is designed to protect the rest of the bone from infection. Granulation tissue usually fills the area between the involucrum and the sequestrum and this tissue then lifts the dead bone up off the healthy bone.

It takes several weeks for a sequestrum to form and be identifiable on a radiograph. Sometimes it is the formation of the involucrum on a plain radiograph that highlights the possibility of a sequestrum forming and additional X-rays over the weeks that follow may be needed to fully assess and determine the appropriate treatment. An involucrum shows as an irregular, raised area of bony reaction on the cortex or outer layer of the bone.

As the process continues, a lytic or black line becomes visible within the involucrum as the sequestrum is lifted off the rest of the bone. Sometimes a draining tract, called a cloaca, can be identified on an X-ray as gas and pus tracts out towards the surface. An ultrasound examination can highlight the possibility of a sequestrum being present when the surface of the bone is irregular, and a cloaca is identified coming from the bone, but confirmation is normally sought using radiology.

Using more sophisticated diagnostic imaging systems can allow a sequestrum to be diagnosed quicker and with more detail but is usually only required in difficult cases. A CT scan provides the best detail of the bone and would be the tool of choice. An MRI could also be used but is less sensitive than a CT scan at detecting the sequestrum. This is because the fragment appears as a low-intensity body of the same intensity as the bone cortex from where it has derived from, so the contrast between the two is less distinct. If there is a lot of granulation tissue between the dead bone and the healthy bone, then the MRI will be able to detect this easily and aid a quick diagnosis.

Though they have their place as diagnostic tools, MRIs and CT scans are significantly more expensive than plain radiographs and require the horse to be transferred to a referral hospital.

Scintigraphy can be used to highlight any inflammation in a bone but is less likely to be used as its major benefit is to highlight areas in the skeleton which are inflamed and could be contributing to a problem. Once a zone of bone inflammation is identified on scintigraphy, the area requires X-rays, scanning or even a CT to give better clarity to the problem. Typically, most areas of bone affected with a sequestrum that requires treatment are readily identified on clinical examination and therefore X-rayed, scanned or CT scanned based on this.

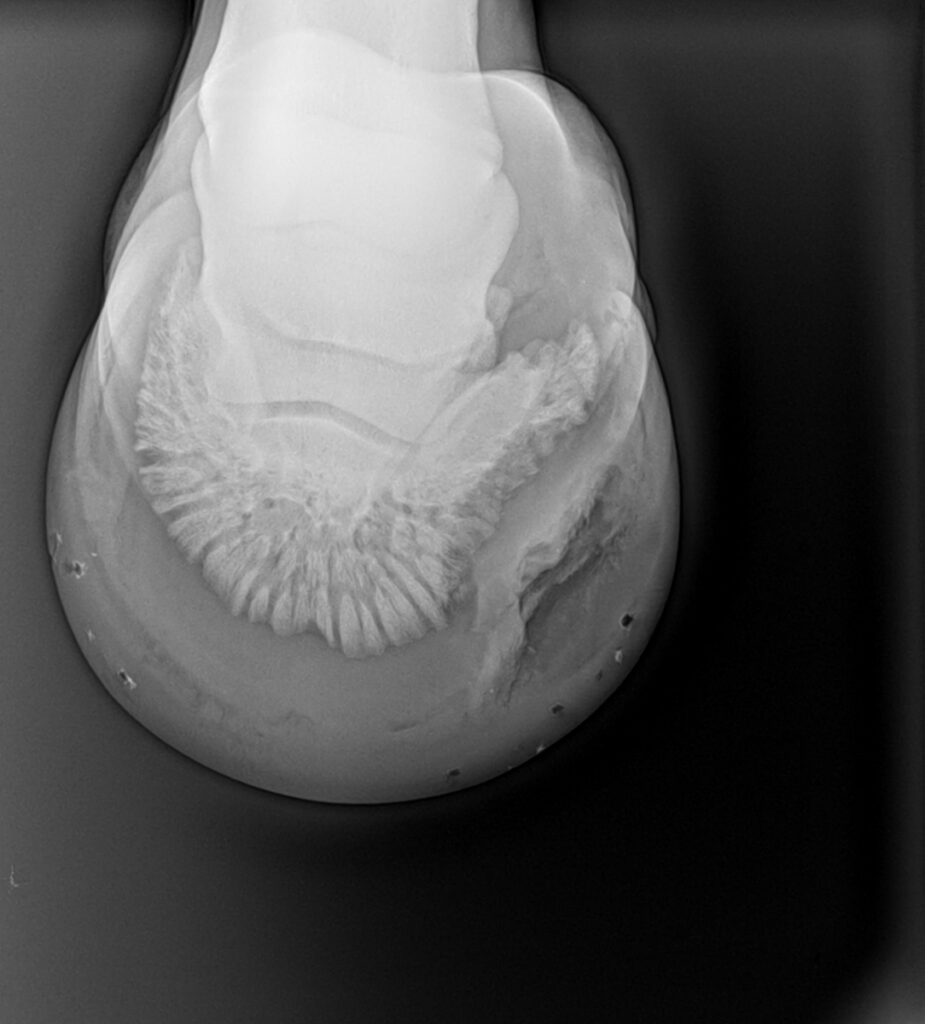

A sequestrum in the hoof; this horse underwent an operation. Image by Advantage Equine.

THE MOST COMMON TREATMENT

Surgery to remove the sequestrum is the most common treatment to resolve the problem. Although antibiotics are often given when a sequestrum is forming, the reduced blood flow to the dead bone often makes antibiotics poorly effective as they cannot reach high enough levels to be of any use. They may be used to prevent osteomyelitis or bone infection occurring, but until the sequestrum is removed the problem will continue to exist.

As mentioned above, the body responds to a piece of sequestered bone in the same way as it responds to a foreign body, by mounting an inflammatory response designed to remove the foreign body from the body. Returning to the filly with the sequestrum in the foot, the filly was extremely lame until surgery was performed to remove a large area of her sole and gain access to the pedal bone. The piece of dead bone was then removed, and the pedal bone curetted and debrided to remove any inflammatory loose material. This left a large defect in the foot that had to be managed by packing the wound with antibiotics and gauze until the wound healed enough to prevent infection getting in and damaging more of the pedal bone.

A hospital plate was added to the shoe to protect the packing and the underlying sensitive sole and allowed for easy access for wound cleaning. The filly’s lameness improved very quickly once the sequestrum was removed.

The same horse from the previous x-ray, post-operation. Image by Dr Maxine Brain.

“Surgery to remove the

sequestrum is the most

common treatment.”

Many other sequestrums, or sequestra, are removed easily by sedating the horse and curetting the bone through the existing wound in the skin. This is particularly true of the small, fine sequestrums that form on the front of the cannon bone after an injury that exposes the bone to air, as occurs after the tendons and skin have been stripped off in a fence injury. In some cases, the wound will not heal properly and the granulation tissue that normally forms over the exposed bone will not completely cover the bone until a fine eggshell thickness of bone is scraped off with a curette or, in some cases, with a gloved finger. Once this happens, the remaining bone typically covers over within days and the horse’s wound heals very quickly.

This horse was successfully operated on to remove the sequestrum. Image by Dr Maxine Brain.

“The good news is

prognosis for full recovery

is usually excellent.”

For a sequestrum that involves a thick piece of bone and has a large, deep deficit in the cortex, the preferred surgical option is to remove it in the standing sedated horse, if possible, as the underlying bone is at risk of fracturing when the horse wakes up from general anaesthesia. This may not always be possible due to the temperament of the horse, making general anaesthesia the only viable option to keep the surgeon safe. In these cases, the owner should be made aware of the risks and the veterinary team take increased precautions to help the horse recover to a standing position.

Not all sequestra need to be removed, however, as some small bone fragments will slowly resorb over time and the infection will resolve without the need for surgery. Once the sequestrum has been removed or resorbed, the body then remodels the involucrum and leaves the bone surface smooth, with only a small thickening on the surface where the involucrum had been. In cases like the pedal bone sequestrum, the bone that has been removed will not reform and the deficit will always be evident on X-rays.

The good news is prognosis for full recovery is usually excellent if the sequestrum is removed and there is no associated bone infection. EQ